A mother’s mission

Amy Brown was the first to get Duke Energy to provide drinking water for her family. But her fight is far from over.

by Audrey Wells

BELMONT, N.C. — Amy Brown walks into her kitchen every morning to prepare breakfast for her 2 young sons. Oatmeal is a favorite in their home, so she grabs a 20-ounce bottle of water from one of the many crates around her home, in order to prepare the morning meal.

For the past 20 months, Brown and her family have not been able to drink or cook with their water due to high levels of arsenic and hexavalent chromium found in their well.

“Normally, you would have taken your pot and filled it up under the sink. We can’t do that, so we have to open up this 20-ounce bottle just to start breakfast,” Brown said. “And my children know now, not to even turn on the faucet when they go to brush their teeth. They open up 20-ounce bottles to do all of that.”

Brown received a “Do not Drink” from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality on April 18, 2015. Her well had been tested by the state, and the results showed that she should not drink or cook with her water. She immediately started making calls to figure why.

“If my well was tested because of how close I live [to a coal ash pond], then this isn’t my fault, I didn’t do anything,” she said. “Therefore, someone needs to provide my family with bottled water, something that I don’t have to fear when I’m cooking my family meals.”

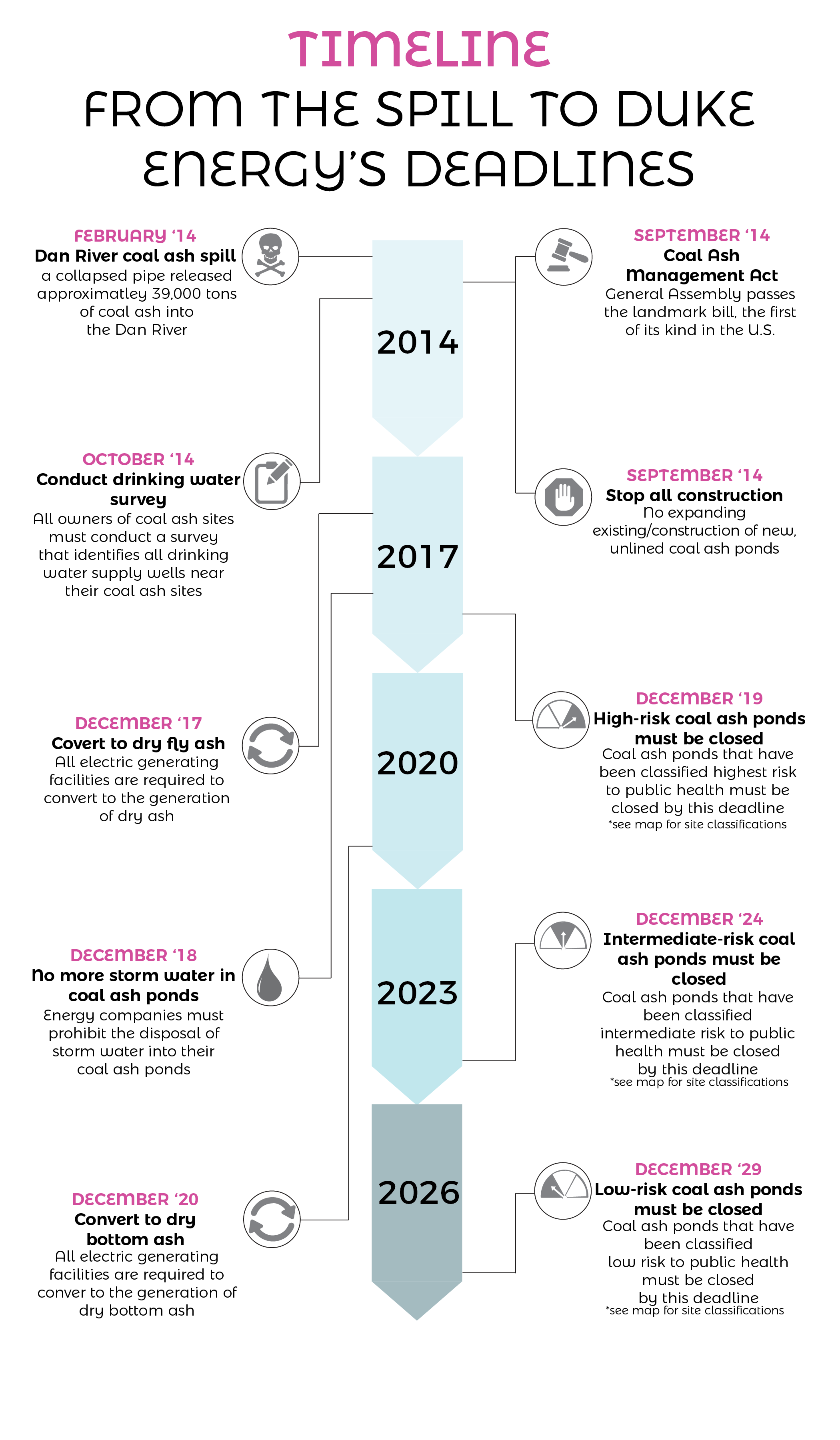

At this time, Duke Energy was in the process of conducting more rigorous testing in that area per the mandate in the Coal Ash Management Act of 2014.

“We were in the process of just beginning the intensive testing that was going to be needed to fulfil the requirements of the state law. And those reports were not finished yet,” Duke Energy representative Erin Culbert said. “Based on the data that we had seen historically, we did not believe that our facilities had any impact on neighbors’ wells.”

Brown continued to call Duke Energy until May 7, 2015 when she demanded to speak to a manager by the end of that day.

“Thursday night, I was on the ball field with my older son in Charlotte and it was getting close to 9 o’clock and my phone rings. And it was the boss over the Charlotte area for Duke Energy, called me from home,” she said.

Tim Gause, the Charlotte region director for government and community relations at Duke Energy, spoke about Brown’s problem and her feelings about the situation. Then, according to Brown, Gause said by giving her family water, the company was taking a risk.

“I quickly let him know what my thoughts on risk were. And that is what about the potential health risk of my children who have been and are being exposed to cancer-causing water,” Brown said. “We’re over here worried about the water that we’re being exposed to and wondering is it safe for our children to take a bubble bath, that’s the difference in how you explain risk and I explain risk.”

Brown said she told Gause he had until Monday morning, May 11, to provide her family with bottled water. And on Monday morning, it was delivered.

Brown has remained an outspoken advocate for her community and those affected by coal ash. She started by hosting community meetings to educate the community on the issue of coal ash. In these meetings, they got information from various riverkeepers, got feedback from affected community members, and even got Duke Energy to speak with them.

Duke Energy said their facilities haven’t had any impact on neighbors’ wells. Culbert said the thorough testing completed in late 2015 confirmed this assertion.

“We continued to see no indication that our ash basins were impacting their wells, and that still remains true today,” she said.

But 20-ounce bottles of water are still an unwelcomed guest in Brown’s home.

“What will your children’s childhood memories be when they grow up? Mine will have the memory of when we lived off of bottled water and what they couldn’t do and how we had to live our lives,” she said.

Culbert said House Bill 630 is the solution for people like Brown who are have been living off of bottled water. The bill requires Duke Energy to provide a permanent source of water for everyone within a half mile radius of these coal ash ponds. The company has until Dec. 15 to propose their water solutions to the state. Then, they will go to the community.

“Community choice and involving those residents is a big part of this process. So we will provide those options back to neighbors and they will have an opportunity to indicate their selection,” Culbert said.

The bill gives Duke Energy until October 2018 to provide these residents with a permanent source of water. Brown said that is too much time. She calls HB 630 the “negotiated bill,” and said it has more downsides than benefits.

“[Duke] can do better than that, especially where I live and the water lines are already there,” she said.

Graphic: How much water does Duke Energy deliver every month?

by Langston Taylor

In addition to the timeline, Brown opposes the option for the cap-in-place method in the bill. She said these pits are unlined and seeping into the groundwater behind her home, and that’s not safe.

As a result of the bill, Duke Energy has agreed to excavate the coal ash from eight of the 14 ponds in North Carolina. Culbert says the company has made the most sensible decision at each location based on the science and engineering.

“I think we can all agree that keeping the material on the plant property itself is really the best option,” Culbert said. “Because otherwise you’re looking for a lot more disposal locations and you have so much transportation needed to be able to move the material to new sites and new locations.”

Still, Brown wants the pond at Allen Steam Station, 1,000 feet away from her home, to be the ninth pond excavated. And she won’t stop until Duke Energy agrees.

“I don’t expect them to clean it up in five, ten, 15 years, I know it’s going to take a long time. I just need them to commit to cleaning it up,” she said. “You can’t tell me my pits are less toxic than the other eight facilities that are going to get cleaned up.”

Until then, she will keep on fighting for her children and their safety.

“No one will fight for my children the way that I will,” she said. “And I am the best teller of my story, and that is why I will continue.”